Florida's Invasive Species -- Chinese Tallow Tree

Part of a Continuing Series

Earlier I wrote about one of the most obvious invasive plant species in Florida — the Brazilian Pepper. Continuing the trip around the globe today we have the Chinese tallow tree. The Chinese tallow tree is sometimes called the popcorn tree and is also known by its scientific name Triadica sebifera. It’s a Class I invasive in Florida and can’t be sold or brought into the state.

The Chinese tallow has an interesting history concerning its initial introduction the US. Benjamin Franklin originally obtained seeds for the tree from his contacts trading in Asia. He saw a need to be able to grow a plant that would allow people to make soap and candles more easily as both were relatively expensive being based on animal fats.

He sent the seeds to a friend in Georgia to grow. As it turned out they were never able to make products from the Chinese Tallow commercially. The waxy seedpods could make candles, but not in the quantity needed to make a profit.

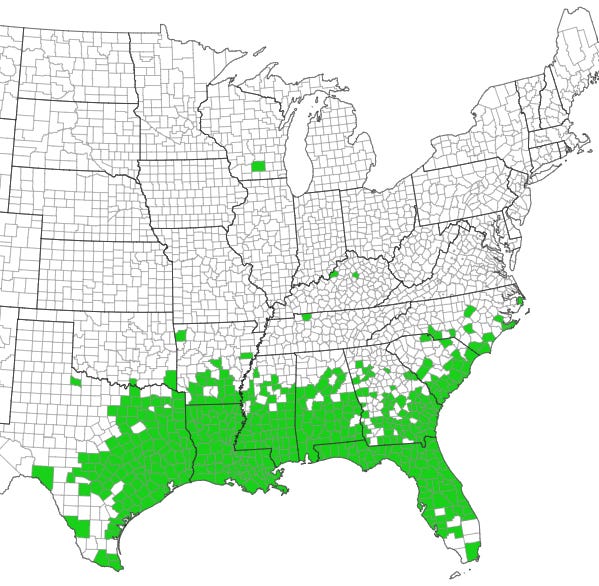

So is old Ben to blame for Florida’s Chinese tallow problems? Actually not. The US Department of Agriculture imported trees in the early 1900’s to study their commercial use. Genetic tests conducted in 2005 prove that Franklin’s trees stayed in a few counties in Georgia. The rest of the trees spreading from Florida to Texas were from the more recent USDA planting. So don’t blame Ben. By the way, 2 other of Franklin’s imported plants were more successful in the US. He may have been the first to import both kale and soybeans from Asia.

The big problem with Chinese tallow trees is just how prolific they are. They can produce 100,000 seedpods in a single year. They simply outbreed other trees in the forest.

The seedpods are relatively small and can be eaten by small birds. They digest the waxy coating and later pass the seed to grow elsewhere. With so many of these interactions happening per tree per year it’s no surprise this tree spreads quickly.

Also the honey from the blossoms are loved by bees.

In spite of all its negative attributes, the Chinese tallow is known for producing large quantities of high-quality honey in many areas of the south. The plant flowers in June and beekeepers often move their hives into tallow tree areas in order to harvest the bountiful nectar.

So Chinese tallows produce plentiful food for birds in late Fall through Winter. Bees love it. An aggressive, fast growing tree takes lots of carbon dioxide from the air. It grows well on banks of rivers and canals that are prone to erosion. And they show wonderful red Fall leaves even in Florida. So what’s the big issue?

They outcompete the natural trees. One study showed they had become the dominant tree in a forest after only 20 years. Chinese Tallow is now the most common tree in the city of Houston, accounting for 23% of all trees in the city. Also they’re toxic to some livestock — goats and sheep love it but cattle can die from eating the seedpods.

Another problem is the fast chemical breakdown of Chinese Tallow leaves. They break down really quickly compared to other leaves. They’re so fast there’s little time for the nitrogen and phosphorus to seep into the soil making them a cause of algae blooms in lakes across Florida.

They’re particularly aggressive on the coastal prairies. In Texas percentage of coastal prairie covered in Chinese Tallow increased from approximately 2% of land area in 1970 to 16% in 1990 to >30% in 2000. In Florida the marsh prairies are already endangered and are being converted to forests by the Chinese Tallow.

I guess the bottom line is the Chinese Tallow tree is here to stay. Governmental agencies can issue plans to eradicate but the reality is it’s too entrenched and too prolific to be removed in the near future. But mostly the pressure will be on owners of wetlands to protect the sensitive areas while allowing growth in other areas.

I write these pieces about invasive species to organize the facts in my mind about how bad the species is for the Florida Environment. I mostly came away from researching the Chinese Tallow confused. Yes it’s a threat to some really precious and irreplaceable biomes. Yes it probably adds some to the eutrophication of Florida lakes. But it also provides great erosion control when most needed and provides food for birds and honeybees.

But in a larger sense it doesn’t matter what we think about whether this new tree is good or bad. Despite the efforts of state and federal agencies it’s here to stay. It’s just too established and prolific to be removed. The only reasonable direction is to protect sensitive environments (especially prairie marshes) and find other way to ameliorate the damages. It’s just not going anywhere.

In this newsletter I’ll be talking about nature, nature photography, natural places (especially in Central Florida) and whatever else catches my eye. If you like this please hit the share button. Or you can subscribe and be notified via email when I post. Thanks for coming by.

Tallow is horrible! And you are right that Houston has a lot of it. It's terrible and no one does anything to mitigate it.